2015 RE-VISITED, PART THREE: Why "Contact" Trumps "Interstellar"

Sometimes, a film pales in comparison to its subsequent borrowers and/or imitators: Inception (2010) bests its obvious predecessor Existenz (1999); The Departed (2006) remains superior to its source material Infernal Affairs (2002); How To Train Your Dragon (2010) surpasses Lilo & Stitch (2002), Kill Bill (2003) over Lady Snowblood (1973), Galaxy Quest (1997) to The Three Amigos (1986). Avatar (2009) ultimately beats Pocahontas (1995), Fern Gully (1992), and Dances With Wolves (1990). Other times however, derivations of pre-existing films fail to improve on their predecessors so thoroughly that it brings into question why anyone would attempt the mimicry in the first place: Yojimbo (1961) obliterates A Fistful Of Dollars (1964); Battle Royale (2000) makes The Hunger Games (2012) look like children’s television; and whoever made Disturbia (2007) should watch Rear Window (1954) again, and then kill themselves.

Contact (1997)—combined with 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), to which an immense amount of credit is due—makes Interstellar (2014) seem like one of the most pointless imitations ever produced; much less an homage to its forerunners than just a soulless composite of everything those films did better. An overwritten, bloated mess of a film, with lazy performances and a narrative so convoluted, hole-ridden, and idiotic that I nearly walked out of the theatre several times. Amazing visual effects and an impeccable score barely saved it from being one of the worst films I have ever seen. Thankfully, having suffered though Interstellar first only heightened my appreciation for Robert Zemeckis’ 1997 classic. It was like eating a dumpster banana peel, then several months later dining at Balthazar.

There aren’t many great science fiction films. Off the top of my head: Blade Runner, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Star Wars (and its sequels), Alien (and its sequel), The Matrix, District 9, Moon, Primer, Gattaca, The Fifth Element, Solaris, Ex Machina, Looper, Minority Report, Inception.

I think I can include Contact on that list because it accomplishes what a great science fiction film should: it asks questions about the nature of humanity and our place in the universe, about the role of technology in shaping who we are as a species, and about how we respond when confronted with the unknown. What impressed me most about Contact was that for a film dealing with no less than humanity’s first interaction with extraterrestrial life and the dichotomy of science and faith… it felt tasteful, composed, and appropriate. And while it explores its themes with total transparency and on-the-nose dialogue, which I would otherwise consider weak writing in most other films, Contact finds an exceptional balance between when it chooses to think and when it chooses to do. Perhaps I’m forgiving the film’s manner of applying its themes directly to the forehead because it’s almost 20 years old, but at the same time it just straight-up knows when to pull back on the ideology and revel in some good ‘ol sci-fi alien thrills.

So when Palmer (Matthew McConaughey) tells Ellie (Jodie Foster) that he can’t support her candidacy for the mission because she does not believe in God, I should’ve rolled my eyes… but I didn’t. It just felt so honest and organic to the material. Carl Sagan wanted to capture what would realistically take place if humanity made contact with extraterrestrials, so OF COURSE someone would bring up God if this actually happened. The film works toward its deepest questions and philosophical concerns with moderation, so when characters start talking about religion, it doesn’t come at you out of left field (unlike say, Anne Hathaway delivering an insufferably ham-handed monologue about love transcending the boundaries of time and space as justification for why they should go find some random person she happens to be in love with or something). Contact approaches this conversation with the type of curiosity and introspection that typifies science fiction; it never shies away from asking important questions, and weaving them into its narrative: in which a scientist who does not believe in God, who firmly believes in data and hard evidence, encounters extraterrestrial life, finally achieving the ultimate goal of her life’s work as an astrologer… but lacking any shred of physical evidence of her experience, must ask the world to believe her on faith and faith alone. Ellie is thus left to wonder if the existence of God comes from humanity experiencing a universe so incomprehensibly vast and extraordinary that it defies rational explanation. Her continued responsibility to the study of science demands that she embrace faith, because faith—in herself, and in the fact that she experienced something real and not in her head—is the only piece of evidence she can cling on to. It’s a perfect conclusion to the film; character evolution effected through beautiful irony.

As opposed to character evolution through: MUUUURRRRRRRRRPPHH!!!!!! MURPH!!!!! MURPH!!!!!!! MURRRRRRRPH!!!!!!! DON’T DO IT MURPH!!!!!!! DON’T LET ME GO MURPH!!!!!! MUURRRRRPH!!!!!!! MUUUUUUUUUUUUUUUURRRRRRRRRRRRPPPPPHHHHHHH.

Which brings me to the elements of Contact that Nolan haphazardly borrowed and bastardized for Interstellar. I say “bastardized” because it seems that what Contact handled tastefully and modestly, Interstellar handled with bloated and unnecessary dialogue and exposition. So in Interstellar, when Cooper (McConaughey) travels to the fifth dimension with TARS and experiences the nature of the universe in ways he never imagined, the following exchange takes place:

TARS: Cooper… Cooper… Come in, Cooper.

Cooper: TARS?

TARS: Roger that.

Cooper: You survived!

TARS: Somewhere, in their fifth dimension, they… saved us.

Cooper: Who the hell is they? Why would they want to help us, huh?

TARS: I don’t know, but they constructed this three-dimensional space inside of their five-dimensional reality to allow you to understand it.

Cooper: Well, it ain’t working.

TARS: Yes it is! You’ve seen that time is represented here as a *physical* dimension! You’ve worked out that you *can* exert a force across space-time!

Cooper: Gravity. To send a message.

TARS: Affirmative.

Cooper: Gravity can cross the dimensions, including time.

By contrast, when Ellie sees the universe in all its glory during her 18-hour journey in the pod through the alien wormhole, she says:

Ellie: Some celestial event. No - no words. No words to describe it. Poetry. They should’ve sent a poet. So beautiful. So beautiful… I had no idea.

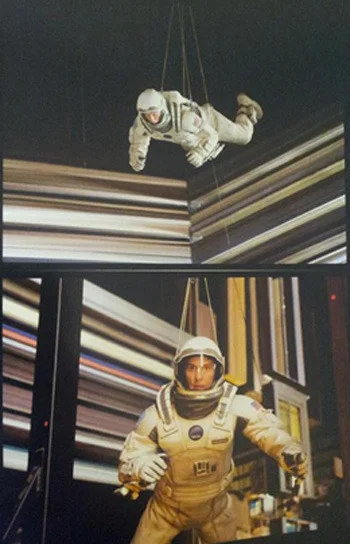

Nolan didn’t seem to understand what she meant by “no words to describe it”—and it’s precisely the words he uses to fucking describe EVERYTHING in Interstellar that makes Contact so undoubtedly superior. Contact shows in all the places that Interstellar tells: Zemeckis asked Jodie Foster to repeat the celestial lightshow pod scene six times, each time with a different expression (joy, fear, sadness, etc.) and then used VFX to morph her face from one take to the next, even using a bit of her face as a child. During the scene, Zemeckis keeps the camera mostly on Foster, and we can visualize her wonder, and then experience it along with her. As opposed to Cooper’s experience in the fifth dimension, which relies more on the accompanying dialogue than what’s on screen to spell out the scene. That said, it’s still a visually stunning sequence, and only that much more impressive that it was achieved using mostly practical effects:

So while the first hour of Interstellar is spent idling with Cooper as he rambles on about how humans should like, really, want to go into space—because it’s not a Nolan film if characters don’t speak their motivations—Contact shows us Ellie’s determination to discover alien life, from the very first shot of her listening to the radio on a pair of headphones.

I think in the end, I’m just really upset with how Interstellar so thoroughly squashed its potential. I expected better from Nolan, and with visual effects that mind-blowing, it could have easily ranked up there as one of the greatest science fiction films ever made. And let’s not overlook Contact, which demonstrates how a modern science fiction film can aim for the stars without sacrificing its grounding.

But then again, it’s hard to disavow a movie with a shot as fucking awesome as this: